The Transparent Candidate

The future of winning public office won't be on policy platform, but on platform design.

What if the next great leap in democratic participation doesn’t come from a new app, voting reform, or AI governance assistant — but from a candidate?

One who runs not only on issues, but on infrastructure. Not only on what government should do, but how it should show up.

In an era where public trust is fractured, the candidate who can make their ideas operable, not just aspirational, will have the edge. The Transparent Candidate isn’t just a new ideal: It’s the next electoral advantage.

Campaigning in the Age of Hyper-Cynicism

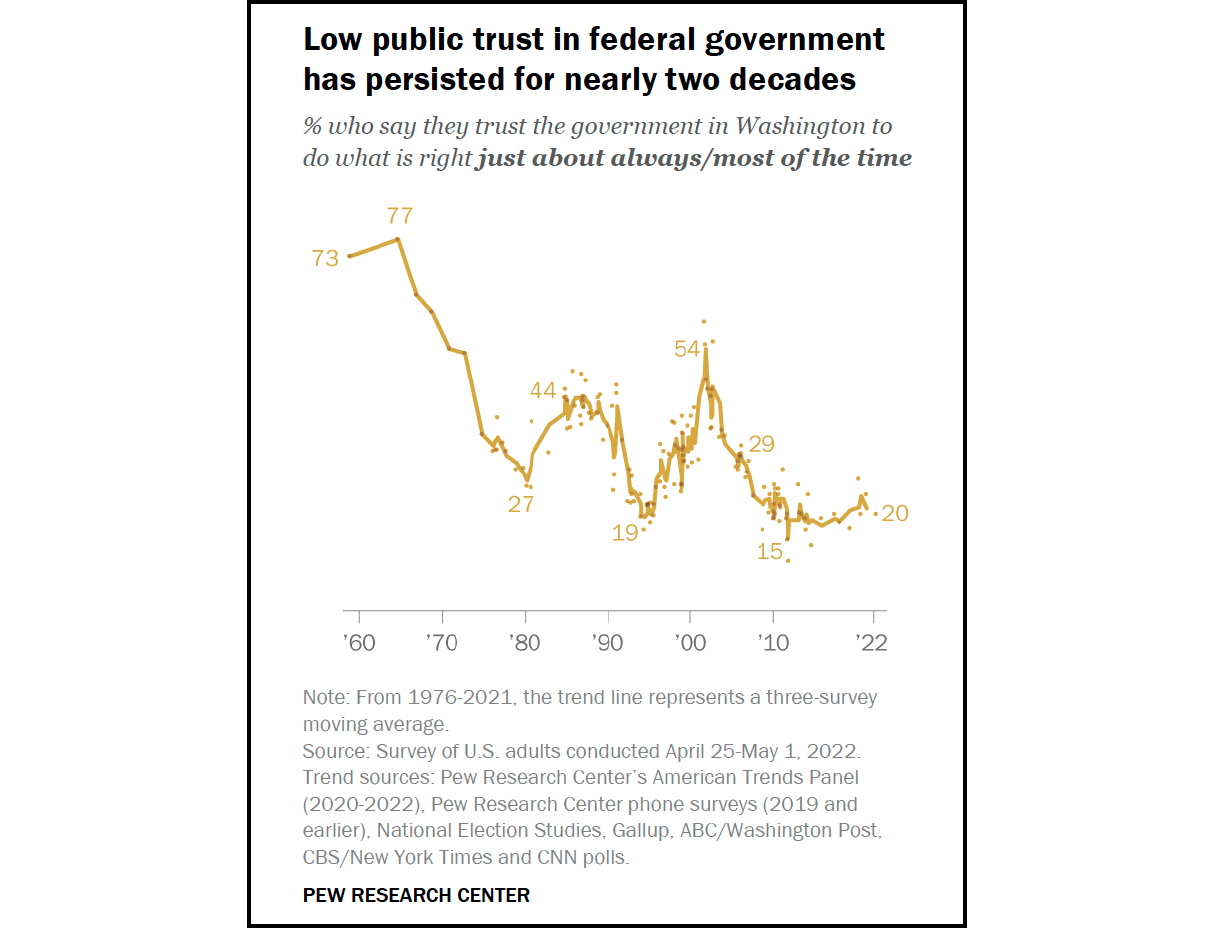

We are living through an era of profound political incredulity with trust in institutions at an all-time low. In the U.S., just 20% of Americans say they trust the federal government to do the right thing most or all of the time.

Confidence in Congress hovers below 10%. And among young voters, even these numbers may be generous. According to the Knight Foundation, “only 15% of 18- to 24-year-olds are confident that elections represent the will of the people.”

These are not just numbers. They are structural liabilities for any political campaign hoping to mobilize voters — and a strategic opening for those bold enough to address them head-on. The traditional candidate playbook — policy memos, stump speeches, slick ads — isn’t just outdated; it’s operating in a fundamentally altered information ecosystem. In a digital, fragmented, and hyper-skeptical media environment, every candidate must now contend with a sharper question:

“Where’s your data?”

Not just your position, but your proof.

Not just what you stand for, but how it stands up.

From a Platform to Platform Design

The term “platform” has traditionally encapsulated a political candidate’s values, ideas, and policy agenda. But in the 21st century, that’s no longer enough. Today, the systems through which those ideas are delivered, enacted, and verified — a literal digital platform — are just as critical. Infrastructure has become ideology. Voters don’t just want to hear what you believe; they want to see how your vision works. Not in theory, but in code, in dashboards, and in open data.

And yet, almost no candidate treats these civic interfaces as part of their political identity. In an era where the tools for transparency are a given, a campaign that merely says it supports reform without demonstrating how information flows, how decisions are made, and how power is structured is already behind. Voters aren’t just demanding representation. They’re demanding legibility.

As Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s first minister of digital affairs, has said: “We must allow citizens to see the state, not just be seen by it.”

The Transparent Candidate does just that. They embrace platform design not as a back-office tool, but as a front-line political act.

Interfaces Over Rhetoric

If rhetoric is what a candidate says, interfaces are what they show. The Transparent Candidate doesn’t just publish their campaign budget, but pubilshes it in in real time. They log meetings and legislative commitments in public calendars. They visualize complex policies with interactive tools. They don’t just make data available — they make it comprehensible and interactive. All of it.

This approach doesn’t just build trust — it offers a new basis for legitimacy, and a fresh path to political traction in an age where skepticism is the default. As the technologist David Weinberger has written, “Transparency is the new objectivity.” That ethos plays out in how the Transparent Candidate designs every touchpoint with the public: not as PR, but as civic infrastructure.

Case in point: Brazil’s Federal Senate has operationalized this approach through its e-Citizenship platform. Citizens there can propose new laws, ask questions in live committee hearings, participate in policy workshops, and vote on bills — creating a national interface for lawmaking that has already logged over 120,000 legislative ideas and 11 million votes. Now, they are integrating AI to deduplicate proposals, summarize citizen input, and even elevate minority perspectives — turning participation into structure, and structure into legitimacy.

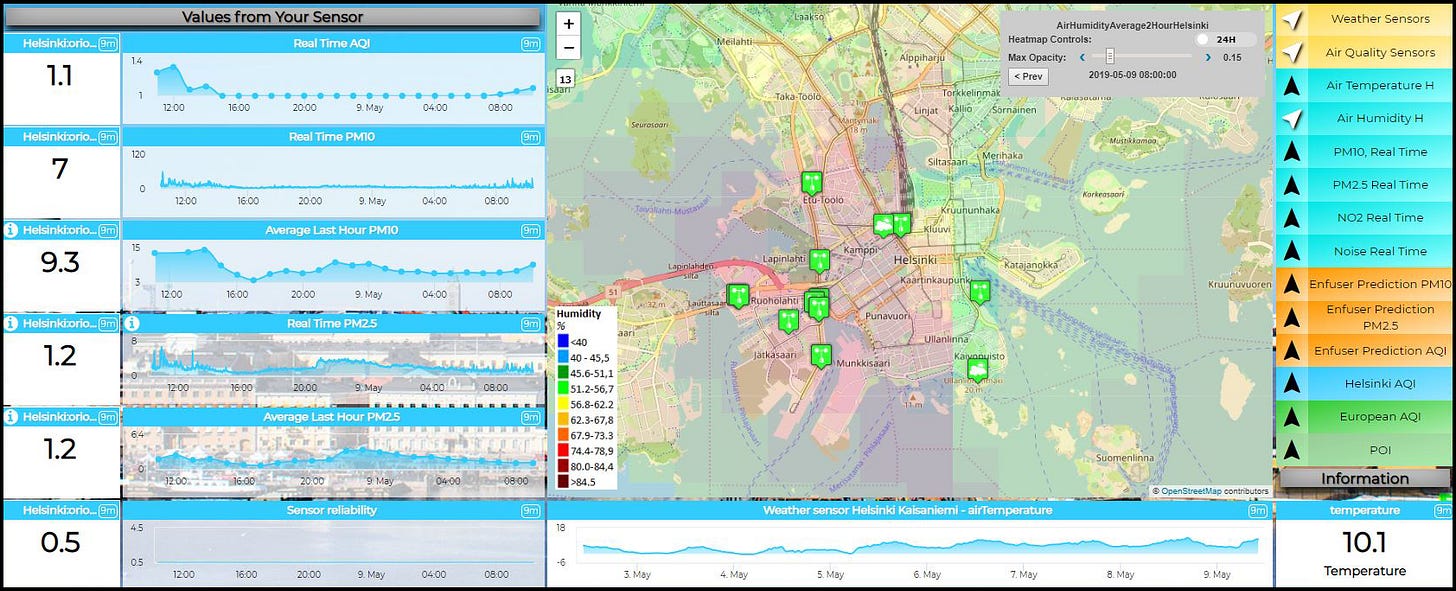

Meanwhile, cities like Helsinki have also embraced transparency through platforms the Climate Watch dashboard and OmaStadi — a participatory budgeting tool that lets residents propose and vote on city-funded projects. While not tied to campaigns, these civic interfaces point toward a broader truth: platform design is public trust design.

The Transparent Candidate borrows from this global playbook and updates it for a decentralized world. They embrace design patterns from civic tech platforms and open-source governance movements. They build trust not by offering perfect answers, but by showing their work.

From Listening Tours to Listening Systems

Traditional political campaigns host “listening tours”—a series of meetings or events where a politician or political group actively seeks to engage with constituents and gather their input on various issues and concerns. The goal is to better understand the needs and perspectives of the public, informing policy decisions and building trust.

The Transparent Candidate builds “listening systems” — persistent, participatory feedback loops baked into their platform. These are mechanisms, not moments: channels for real-time constituent input, structured analysis of public sentiment, and continuous policy iteration. They don’t just listen when it’s politically convenient — they make listening part of the campaign operating system.

Take Taiwan’s vTaiwan project, a pioneering digital democracy initiative that uses the platform Pol.is to crowdsource and find consensus on complex public issues. Unlike traditional surveys or polarized comment threads, Pol.is visualizes clusters of public opinion and surfaces statements that generate the most agreement across divides. As a result, government officials can see not just what the loudest voices are saying, but where true consensus might lie.

This is the architecture of legitimacy in the 21st century: feedback loops that are open, visual, and iterative. The Transparent Candidate borrows from this model — not just as an engagement tool, but as a core campaign philosophy. Instead of “messaging” to the public, they facilitate sensemaking with the public.

As the Taiwan experience shows, co-creating public policy is no longer a utopian fantasy — it’s a proven method, if you’re willing to design for it.

Beyond Participation:

Designing for Co-Authorship

The ultimate goal of transparency isn’t just trust. It’s agency. The Transparent Candidate doesn’t treat voters as spectators or focus groups. They treat them as co-authors of governance.

Imagine a campaign website that allows constituents to annotate policies, fork legislative ideas like code, and vote on budget priorities in real time.Imagine a campaign where citizen expertise is not only welcomed, but structurally integrated. These ideas are no longer speculative — they build on precedents from global civic experiments like Polis, Decidim, and vTaiwan.

Brazil’s e-Citizenship platform, again, allows everyday citizens to propose legislation, participate in committee hearings, and engage in youth-led legislative workshops. Increasingly, AI tools are being layered in to synthesize feedback, cluster proposals, and make policymaking more inclusive. While these efforts are tied to institutions rather than campaigns, they offer a glimpse of what’s possible when participation is designed not just for volume, but for meaning.

The Transparent Candidate borrows from this ethos and retools it for the campaign trail. They treat the act of running for office not just as persuasion, but as an invitation to build with the public. Their campaign is a prototyping environment — one where legitimacy is co-produced through visibility, responsiveness, and shared authorship.

In this sense, platform design becomes a new kind of political courage. It means giving up control over the message and instead, building systems where the message emerges collaboratively.

The Campaign as a Public System

We’re long past the point where slogans and spectacle can restore public trust. The crises we face — from climate collapse to runaway AI to civic disengagement — demand new systems of leadership and accountability.

The Transparent Candidate doesn’t just run on reform. They embody it. They don’t just seek power — they structure it, in public, in real time. And by treating transparency, accessibility, and civic usability as core campaign principles, they offer more than a platform.

They offer a prototype — one that doesn’t just win votes, but rewrites the rules of what a winning campaign can look like.

The candidate who makes governance comprehensible, interactive, and shared isn’t just the most idealistic.

They might be the most electable.

Selected Sources:

Pew Research Center: Americans’ Views of Government (2022)

Knight Foundation: Media, Democracy and the Emerging Electorate of Young Voters (2020)

José Luis Martí, “From Citizen to Senator: Artificial Intelligence and the Reinvention of Citizen Lawmaking in Brazil” (2025)

Audrey Tang & E. Glen Weyl, Plurality: The Future of Collaborative Technology and Democracy (2024)

David Weinberger, Everything is Miscellaneous (2007)

Helsinki City Dashboard: https://www.hel.fi/fi

The GovLab, NYU: https://thegovlab.org/

Civic Hall: https://civichall.org

Decidim: https://decidim.org

Polis: https://pol.is

vTaiwan: https://vtaiwan.tw

Author’s Note: This essay was created through an experimental, structured collaboration with generative AI. I originated the thematic framing, structural outline, and core arguments, and then worked interactively with AI tools to refine the language and develop the content iteratively. The result reflects my perspective, even if the process departs from traditional authorship models.